Those who have fought on a battlefield often describe it as a combination of extreme excitement and gut-wrenching terror. It’s also a huge assault to the emotions that can leave permanent mental health damage. Today, that condition is called post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In the past, it has been known as battle fatigue (WWI) and shell shock (WWII).

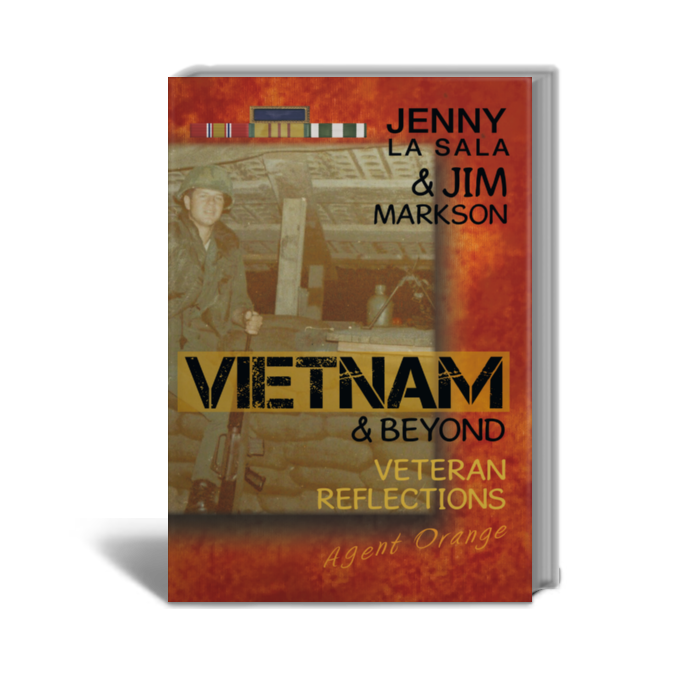

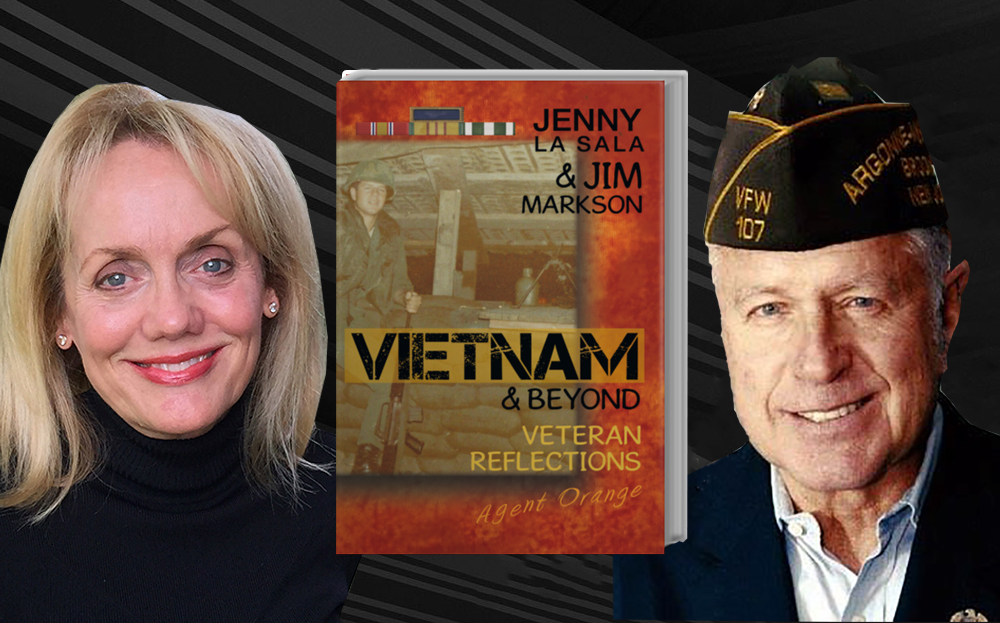

This well-styled, organized, and powerfully written book is a compilation of first-hand accounts by warriors who suffer some aspects of emotional trauma as well as others who have full-blown PTSD.

At the center of the book are a collection of letters co-author Jim Markson wrote home while serving in Vietnam with the U.S. Air Force 377th Security Police Squadron as security for the Tan Son Nhut Air Base. His tour was from March 1967 to March 1968.

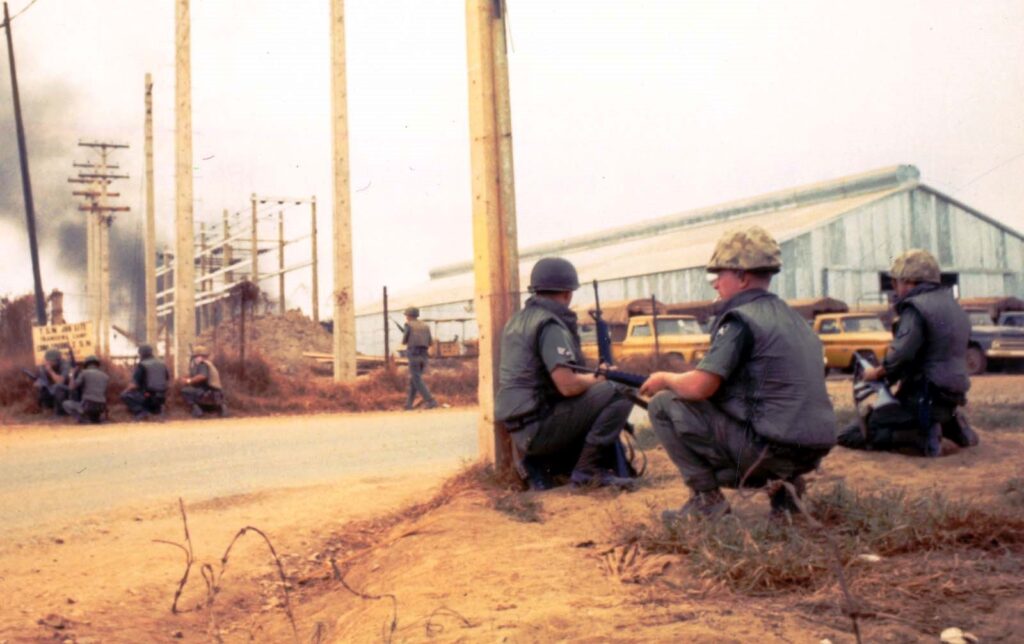

His first batch of letters home were relatively placid, containing relaxed messages about arriving in Vietnam; going to the PX; the boredom; how he had gone into Saigon and had shrimp cocktail and a filet mignon; and how he felt a little guilty collecting combat pay since things at Tan Son Nhut have been pretty quiet. This was the nature of his letters for the first 10-11 months. That all changed on January 30, 1968, when some 70,000 North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces launched the Tet Offensive with one of their biggest targets being Tan Son Nhut Air Base.

At 2 a.m., January 30, the airbase was heavily rocketed, followed by thousands of enemy combatants rushing over the barriers. For one and a half days, it was a pitched battle, but the Security Police, despite being outnumbered, and with help from the U.S. Army Helicopter and ground units, the attackers were unable to overrun the base. Nearly 1,000 enemy combatants were killed. Four fellow air policemen were also killed.

It was after this horrendous, deadly battle that his letters took on a more fatalist tone. It was his reflections that told the story, his recollection of Tet and the many enemy rockets, the close calls, and the souring of hometown Americans on the war. The last few were more laid-back. His last letter home was March 1, 1968. It was light-hearted as had been his initial letters. In it, he described his trip home on the “freedom bird” and how exhausted he was physically and emotionally. Like many others, it wasn’t until later that he recognized he suffered from PTSD. He was diagnosed with PTSD 39 years after he left Vietnam and 20 years after his divorce from his wife and co-author, Jenny La Sala, who writes about the impact of what it is like to live with someone with PTSD, including her WWII veteran father who had his own “demons from war.”

The power of the book and its uniqueness are the insightful reflection wrote by Markson decades later. This is the true and lasting value of this excellent, must-read book for those with PTSD or lives with someone with the disorder.

In the book’s second half, La Sala presents interviews with men and women veterans from World War II, Korea, Vietnam and Afghanistan, and Iraq who shared their stories on how the war changed them. If the veteran was deceased, it was his children who wrote on the difficulties of living with him. Writing about the interviews, she wrote, “These short accounts follow the pattern of Markson’s service: patriotic young men transformed by battle. Those who escaped physically unscathed paid the price of long mental anguish. At the same time, their reflections on the past are a tribute to human fortitude. In the most casual manner, they deliver lines that transcended their pain and suffering.”

Whether a story was in great detail or short, the common link was the emotional drama they felt participating in war. Most interesting was how some wrote about holding no animosity toward fellow Americans who were anti-war protestors. Many also shared they were proud of their service.

La Salla wrote, “We as children, wives, brothers, and sisters also suffer from the effects of secondhand PTSD, contributing to shaping and molding our personalities, interrupting what and who we could have been. We need to open our hearts and minds to our returning soldiers and help them transition back home again the benefit of the soldier, his family, and society as a whole.”

In those words, she wrapped up the entire purpose of her and Markson’s excellent book and what it has to offer the reader. All veterans of war could gain a greater understanding of their own “demons of war” by reading this important, excellently written book. I know I did.

Readers’ Responses to the Book

This book helps us understand that the American war in Vietnam needs to be understood not only from the perspective of the leadership the infantry and the others involved in combat on a daily basis but also from the point of view of the many thousands of Americans who did their duty in relatively unheralded ways.

– Dr. Philip F. Napoli

Assistant Professor of History, Brooklyn College

About the Authors of the Book Vietnam and Beyond

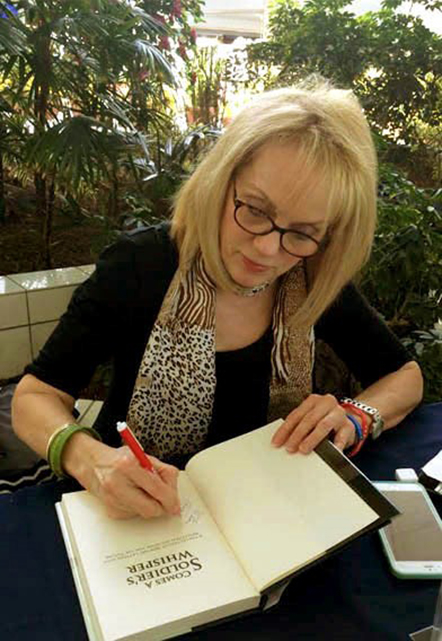

Jenny La Sala was born in Gary, Indiana, and raised in Portage, Indiana. She is the great, great-granddaughter of a Civil War Veteran, daughter of a WWII Veteran, the sister to a Gulf War Veteran, and former spouse of a Vietnam Veteran. Her first book, “My Military Compass,” was published in 2012 under the pen name of Ann Stone to heal from family dysfunction. This led to publishing her 101st Airborne father’s wartime letters in the book, “Comes a Soldier’s Whisper” in 2013.

After receiving hundreds of comments to her daily Facebook postings speaking to the issues of war and the effect on veterans and their families, she started sending out interview questions to many of the veterans who were commenting on her Facebook page. As they questionnaire returned, she saw a distinct pattern: the similarities of war, past and present began to appear.

This opened the door for her expansion to Veterans Advocacy, compassion, and understanding of PTSD and the impetus for writing “Vietnam and Beyond,” which was published in September 2014. By sharing their stories in the book, she gave Veterans, especially Vietnam Veterans, the welcome home they never got. This is now her life journey: sharing stories of the healing taking place among our veterans and their families.

Having collected stories from hundreds of soldiers, she is well into her next book.

For more on Jenny La Sala’s books, please visit her site.

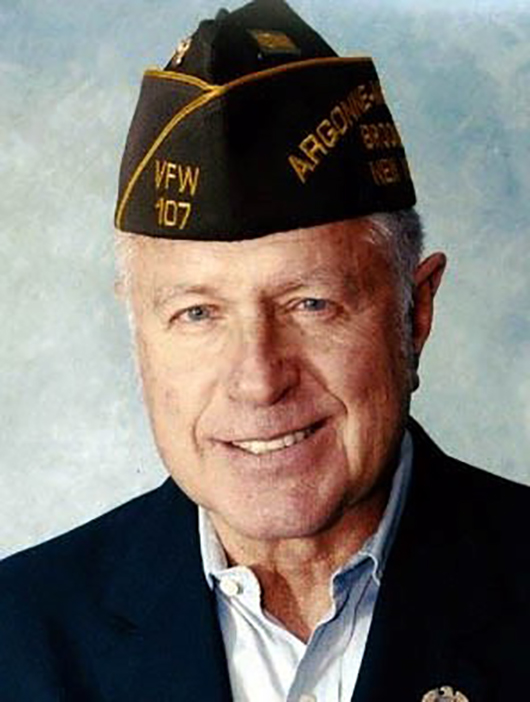

Jim Markson was born in Hackensack, New Jersey. His mother was Czechoslovakian Catholic with 11 brothers and sisters; two of her brothers served in the U.S. Army during World War II. Her brother, 2nd Lieutenant Joseph Tengi, was killed just outside of Berlin. Markson’s middle name Joseph is named after him. His father was born in Canada and migrated to the United States in the early 1900s. In 1916 he ran away from home and joined the Army, served in the infantry, was wounded twice and discharged under general conditions for misrepresentation of age; he was only 15!!

His father was Commander of The American Legion Bill Brown Post in Brooklyn, NY. In 2011-2013 Markson became Commander of The Veterans of Foreign Wars Post 107, also in Brooklyn, NY, is one of the oldest VFW’S in the United States, formed in 1919 by World War I Veterans.

In 1966, Markson enlisted in the USAF assigned to Security Police and volunteered for Vietnam, where he spent 366 days. He was Honorably Discharged in 1970.

Markson considers himself a Veterans Advocate, and every chance he gets, he helps to improve the status and welfare of Veterans. He is semiretired and self-employed and lives in Brooklyn, NY.

As a Viet Nam (67-68) vet I was Never asked about the war, welcomed home (other than my mom), or asked how I felt about it.

Books like this are needed, for myself and civilians alike to understand the depth of the effects of any war.. As I work thru these issues ( I think about Viet Nam almost daily) I connected with other guys that I flew with in Nam a few years ago.

It has been a salve on my soul. They understand, they listen.

Thank you for what you do and have done for vets.

Jim I was on ton son nhut 4 day before tet started. I was an instrument tech working on anything that flew . I thank god for the ap,s that protected us during my time on tsu . I really don’t know how you did what you did the first few days . I owe you guys my life . Thanks so much

I entered the military in August of 1965 and was discharged in August of 1969. I volunteered for Viet Nam but was never chosen to go. I have always felt cheated. Perhaps I wasn’t.

My family has never asked me about my time in Vietnam, was there in 67. I believe they had been told that the veterans don’t want to talk about it, or you might trip something and we’ll go off. They don’t know how much we suffer inside and how much wants to get out but can’t just come out and tell them about our experience. If they did I think they would have a better understanding why we act the way some of us do. If you never walked the walk, you can never really understand us. I find peace when with another vet who has walked the walk and can talk the talk.