In 1973 a devastating fire in the National Personnel Records Center destroyed about 17 million military personnel files. A loss with long-lasting repercussions, it affects our understanding and knowledge of many individual WWII stories.

The Fire at the National Personnel Records Center

Here in New Orleans, the destructive power of fire and especially water is well known. Large disasters such as floods, earthquakes, and fires affect our national consciousness, and their devastating power often goes beyond the destruction of buildings and landscapes. In many cases, invaluable records, images, and other memories of human experience are lost in their wake. One such disaster affects our understanding of World War II to this day in that it took millions of records of those who fought it: the 1973 fire at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis.

Design Flaws in the NPRC and the Fire Hazard

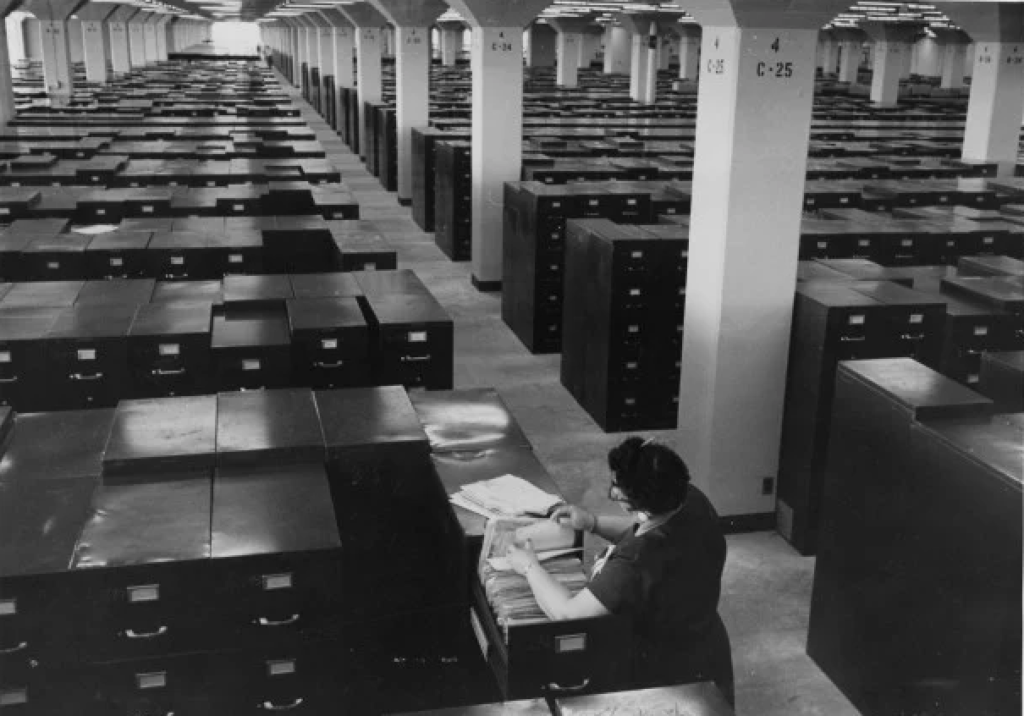

The National Personnel Records Center was formed in 1956 in an effort to streamline archival processes and merge several archival agencies. Its key job: to house and handle service records of all persons in Federal civil or military service. For that purpose, and after consulting complex and extensive architectural and archival studies in best practices, the Department of Defense constructed a six-story building outside of St. Louis, MO. By 1973, the NPRC had amassed about 52 million individual personnel records.

Despite being state-of-the-art, the center had two major flaws, and both would prove fatal almost two decades after it was built: the building lacked both a sprinkler system and physical barriers to any potential fire. Counter-intuitive to modern thought, key figures in the building process lobbied against a fire-preventing sprinkler system in the archival center. The fear of water damage due to potential leaks and or piping issues was stronger than the fear of fire. Further, the building’s interior had very little to offer as a safety net against spreading flames. There were no firewalls or other barriers in the large open work and storage areas, filled to the brim with flammable materials.

The Devastating Aftermath of the Fire at the NPRC

These two flaws exacerbated the disaster that started to unfold on the night of July 12, 1973. One with repercussions that last well into the twenty-first century:

The first calls received by the Olivette Fire Department came in at 16 minutes past midnight on July 12. The top floor of the NPRC building was on fire. The dispatched firemen quickly reached the Center and were able to access the sixth floor, which was determined to be the main location of the fire. However, fighting from within the building became harder and harder until the firefighters finally had to withdraw from the smoke and heat at 3:15 a.m. The blaze was so severe that local residents were urged to stay inside to not take in too much toxic smoke.

The firefighters fought an uneven fight. For 22 hours, the building burnt uncontrollably. To make matters worse, low water pressure and failing pump trucks interfered with the operations and hampered the pouring of millions of gallons of water into the raging fire. Despite these obstacles, the participating 42 fire districts were able to contain the fire eventually and keep it from spreading to other floors. After two days of continued firefighting operations, firefighters re-entered the building, and four days later, on July 16, the fire was officially considered fully extinguished.

The cause of the fire was never found, even though investigations began while firefighting activity was still ongoing. The FBI looked into the possibility of arson, but no evidence was ever found. People that had been on the sixth floor shortly before the fire reported that they didn’t notice anything wrong or different, nor were mechanical causes ever found. To this day, the source of the fire remains undetermined.

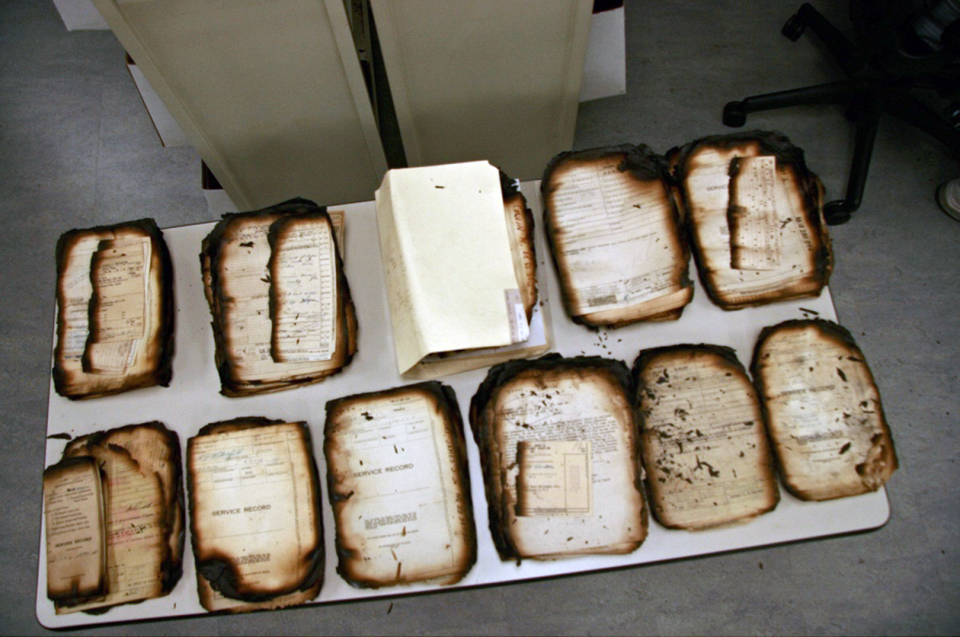

Once the fire was finally extinguished and the fire trucks left the premises, the painstaking retrieval and restoration work began. Fortunately, no one was injured, but the loss of records – and with its historical memory – was devastating. The sixth floor was a scene of absolute and total destruction. The fire had caused the roof to collapse onto itself; the intense heat mangled metal shelves and filing cabinets, rows and rows of records were reduced to ashes, and water and debris were everywhere.

Retrieving and saving as many files as possible from the rubble and destruction proved chaotic and difficult. The St. Louis summer heat and humidity in combination with the water damage created a situation in which quick and proper action was necessary to avoid further damage to the files by mold growth.

This was a monumental task: damaged records were retrieved from the building as quickly as possible on makeshift ramps, and preliminarily held in a quickly built tent city on the National Personnel Record Center’s grounds. From here, they were put through a drying process, which included spraying with preservative thymol solution, laying out in drying racks, and keeping them in milk crates, which proved to be the most beneficial storage.

The volume of wet records was immense: almost 90,000 cubic feet of documents needed drying.

Vacuum chambers in the nearby McDonnell Douglas Aircraft Corporation plant used for the Apollo space program spontaneously and surprisingly became the saving grace for many records after initial tests showed good results using vacuum technology to dry wet records. About 2,000 milk-crates of documents were put in the chambers at a time. Rapid temperature change inside the chambers retrieved about eight tons of water in each session. In doing so, the records were saved from further mold damage. The fire and water damage that the records endured, however, remained.

All in all, about 80 percent of the military personnel files of Army and Air Force service members that were housed on the sixth floor were lost for good. Navy, Marine, and Coast Guard files were mostly spared. Only those that had been actively worked on were on the sixth floor at the time and hence lost. Of the roughly 22 million individual files that were stored on the sixth floor of the facility, only about 4-6 million survived, 16-18 million were destroyed. This vague number is due to the fact that the records had not been indexed, microfilmed, or ever duplicated, so there was no database or registry to help check the losses against.

The official numbers put out by the National Archives claim that 80 percent of Army personnel discharged between November 1, 1912, and January 1, 1960, were affected by the fire as well as 75 percent of all Air Force files of personnel discharged between September 25, 1947, and January 1, 1964 (with names alphabetically after Hubbard, James E.)

After the drying process, most records were stored and left untouched – until they were requested or until budget and technology would become available to help make more sense of these documents in various degrees of degradation – some charred and burnt, brittle from the fire, others fused and held together by remnant mold and debris.

Recovering and Reconstructing Files After the Fire

The NPRC’s work has continued despite, and stimulated by, the tragedy. Restoration and reconstruction efforts have been a key activity at the NPRC to the present. The Center’s treatment lab uses the latest technology to make previously considered lost files legible again. However, no matter how technologically advanced the methods of reconstruction have become over the years, the sad reality is that the vast majority of records affected by the fire were completely lost. Ashes cannot be made legible again. In these cases, documents that were not originally stored with the rest of the file (referred to as Auxiliary Records) are used to reconstruct basic service information needed for veterans’ benefits, burials, and other matters tied to an individual’s military service.

The research procedure, both in the National Archives as well as for anyone working with these files, is complex, multifaceted, and time-consuming. The information-gathering process can be very rewarding, offering insights into a person’s life during wartime and military service. Unfortunately, in most cases, auxiliary records and other documents can only tell part of the story. The human story, the history of an individual, from basic training through the various stages of his or her military service as found within the many files and forms, is often forever lost.

Source: National WWII Museum

Read About Other Military Stories

If you enjoyed learning about the significance of fire in the National Personnel Records Center, we invite you to read the stories of other remarkable stories on our blog. In addition to our profiles of celebrities who served, we share military book reviews, veterans’ service reflections, famous military units and more on the TogetherWeServed.com blog. If you are a veteran, find your military buddies, view historic boot camp photos, build a printable military service plaque, and more on TogetherWeServed.com today.

I enjoyed reading this article. Recently I have written to the Pentagon and the President regarding my neighbor who passed away April 16, 2025. His name was Paul Maurice Millholland, Staff Sergeant, died at 91 years of age; Enlisted on October 10, 1954 (Service Number ER164 93 551), On active duty at Fort Benjamin Harrison as a Military Police Officer and was honorably discharged October 10, 1962 (8 years total service). He was discharged by the 415th Civil Affairs Division at Kalamazoom Michigan. Unknown which unit but it may have been with the 226 MP Company. His Social Security Number is 309-32-4892. Born March 17, 1934. I also wrote to the VA and Congressman Jacky Rosen (NV), to the National Personnel Records Center, Department of the Army, U.S. Army Reserve Personnel Center Support Command, 415th Civil Affairs Divisionand the U.S. Department of Labor (Claims Control Center). I have a copy of his discharge and an image of him in uniform. His widow had to go out of pocket to bury him, she can’t refinance her home using the VA, and no one will even provide her the medals and ribbons that her husband earned while in service. She is divistated. Can you help in any way? My number is 702-333-8490 Thank you, I went out of pocket some $300.00 to have a laser wood wall hanging with his information so she has something to look at over his now empty desk.